Amongst Pilar Cossio’s works there is a surprising drawing that shows part of a woman’s dress. The framing chosen by the artist fixes the eye on the bust and pelvis of the model. The waist marked by a subtle belt, beautifully knotted, divides the surface half way up at the same time as displacing the image to the left as if by mistake, the focus were about to allow the motif to escape from the picture.

Strangely, the exceptionally delicate.outlines, compulsively are however accumulated compulsively in order to form a dark patch just where the material, like the shawl crossed over her bosom , hugs the left breast of this female body barely hinted at, becomes apparent and captures us.

The outlines coming together in wide waves seem to flow from the top right hand side which this way concentrate all the gravity of this special image, immediately acquire a kind of autonomy. After a prolonged look the initial meaning is lost and they are converted into locks of hair or river flows or a current .That vitality would drag all the image in its flow if it weren’t suddenly interrupted by a vertical line which marks the meeting with the other half of the dress, symmetrically covering the left breast. but more discretely. There are other lines, given minor importance, which added to the drawing , are of an apparent anodyne aspect, and immediately reveal, deceptively this time ,another divergence of a paradoxical photographic nature: to the right the outlines of the woman’s body , or rather of her dress, are double as if by one of those focal effects of being out of focus, that is sometimes produced unwillingly whilst we are photographing.

To tell the truth, Borderline (such is the title of the drawing of the dress) is not Pilar Cossio’s only work based on the double image. We can find other forms in other drawings, the one named Bahía Arco Gas or in the picture Autour les choses with the image of the girl or even more explicitly in a work , this time photographic, entitled Hamburg N, that shows a human figure (an androgen, a man?) cut at the upper part at the level of the lips, and below where the superior part of the breast begins.

These images can help us to resume some of the feelings that Pilar Cossio’s art simply can’t avoid arousing. In fact in her work, bodies are only revealed to the spectator from the absence or an eclipse, disappeared or about to do so. Always on the move, we are only left with the fleeting traces, or if stable, they are only metonic.

We shall return later to this last detail, but only after pointing that , at any rate, there are very few faces and that when they do appear, as in the case of the girl in Autour les choses, , they seem to arise to from an interior vertigo which projects them to an even more insurmountable distance, as if they belonged to another diaphanous world.(In the case of Autour les choses, this sensation is even more so accentuated by the overprint as the picture is covered with an image , perhaps photographic, which shows a house, a fir tree.)

Only in this other world- transported in time and only alive in our memory-could these women the only remains of which are those metonic traces and above all those beautiful, magic pointed shoes clouded by a surgical aura (Plexiglas and aggressive metallic armbands) that Pilar Cossio never ceases to show us. As regards these cold, but intense exhibitions, some people would even dare to invoke the Freudian tradition and the article of 1927 where the famous declaration made by the founder of psychoanalysis appears: “I am surely going to cause disappointment by saying that the fetish is a substitute for the penis.”

Besides adding the following precision whereby the fetish is not the substitute of just any penis, but is “woman’s (the mother)phallus in whom the boy has believed and whom , we know not why, he is not willing to relinquish.”

Also, further on in the text, Freud explains that the foot and the shoe are “the favourite fetishes”, precisely because “the boy has spied on the woman’s genital organs from below, viewed from the legs”, such a Freudian interpretation of Pilar Cossio’s works would be to lapse into the anecdote and the stereotype.

It is evident that the metonym on which it is elaborated, remains absent , but not necessarily in that ending in castration, the so called reversed destiny of femininity. And , if we have to invoke the fetish, it would then be advisable to do it from the magical angle before Freud’s time, that facet, so well perceived by Binet, the other “soul” doctor, according to whom “everybody is more or less fetishistic where love is concerned” and that to believe in J.-B. Pontalis’s written work, he knew how to recognise in “sexual fetishism”, more than an aberration of love, its secret , In this way, therefore the fetish justifies the adoration , in the same way that the supposed primitive adores his own in virtue of the mysterious powers attributed.

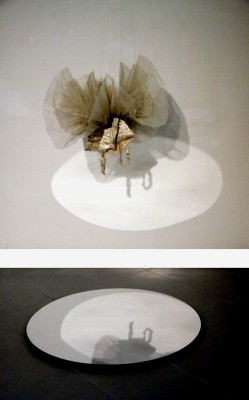

In other words ,in Pilar Cossio’s work it is herself , not her cut off penis that has gone , gone from those beautiful pointed shoes, in the same way as the Pavana dancer has abandoned her tutu and once free henceforth floats in the air clouded by a halo of light whilst on the ground a circular mirror transforms her interior into an abysm. Apart from that , who knows if it weren’t through this mirror that the ballerina escapes, in order that, eternally we note her absence?

DANIEL SOUTIF

PARIS. February 2006.

Freud’s article on Fetishism is totally reproduced in Number 1 Objects of Fetishism in the New magazine of Psychoanalysis (autumn 1970) from where Binet and J.-B. Pontalis’s quotes are also taken.